Difference between revisions of "Real electronics"

Steven Nagle (Talk | contribs) (→Real electronic breadboards) |

Steven Nagle (Talk | contribs) (→Real capacitors) |

||

| Line 62: | Line 62: | ||

==Real capacitors== | ==Real capacitors== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Real capacitors include a small but sometimes relevant resistance in parallel with the ideal mode of capacitance. This resistance will be specified on the datasheet for the capacitor. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Electrolytic capacitors have a preferred polarity and cannot support a large current. Thus they are only to be used for DC voltages with small AC fluctuations. If they are installed in reverse polarity, then at best they will function poorly and start to stink as the rubber wadding melts or at worst they will explode and shoot someone's eye out.<ref>For more information on why this is a bad thing, please see [[http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0085334/ ''A Christmas Story.'']]</ref> | ||

==Real op-amps== | ==Real op-amps== | ||

Revision as of 22:25, 24 August 2013

Real electronics sometimes behave significantly different than the idealized models presented in lecture.

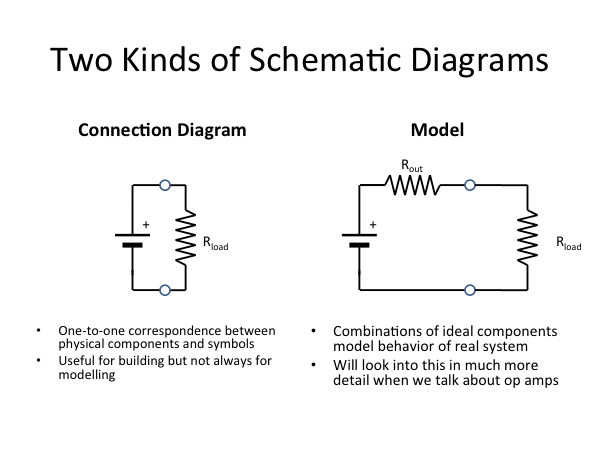

Real power supplies

Limits of ideal elements: more realistic model of a battery

Recall the ideal i-v curves for our four elements, referring to Table 1 under Primary definitions .

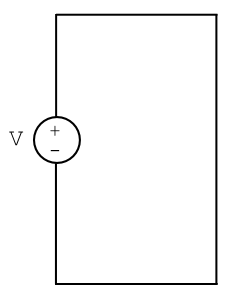

Let’s model a battery as an ideal voltage source connected to no other elements except ideal wires (Fig. 14).

What is the current flowing through this circuit? The resistance of the wires is zero, implying that the current is infinite! Therefore this model, and the associated horizontal i-v curve, is not realistic.

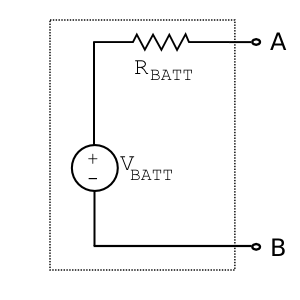

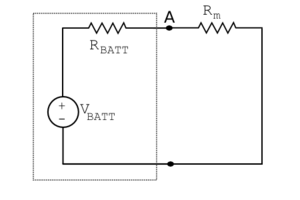

Instead, let’s model the battery as having an internal resistance, $ R_{BATT} $ (Fig. 15). To investigate the i-v curve, we’ll view the output port formed by nodes A and B.

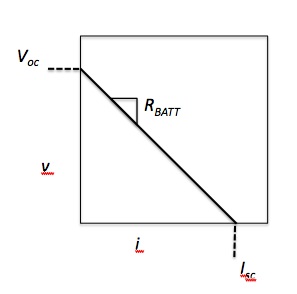

When the port is not connected to anything, resistance is infinite and current is zero. There is no load on the battery, and thus the output voltage at node A must be the full $ V_{BATT} $. This useful quantity is our by now familiar open circuit voltage, $ V_{oc} $.

Next, let’s attach a voltmeter to the port with an associated resistance $ R_m $.

When we assume that $ R_m = 0 $, $ v_A $ is shorted to ground. Thus, the current i is at its maximum, namely the short circuit current:

$ I_{sc} = \frac{V_{BATT}}{R_{BATT}} $.

These two quantities define two points on our new, more realistic, i-v curve! Presumably a line connects them, but let’s prove it by solving this simple circuit. We’ll practice our systematic approach once again.

The only unknown node voltage is $ v_A $. The other nodes are either ground or $ V_{BATT} $ by definition of a perfect conductor. Hence we want to solve KCL at $ V_{BATT} $, substituting in the relevant $ v=iR $ constitutive relations:

$ i1 + i2 = 0 = \frac{9-v_A}{R_{BATT}} + \frac{0-v_A}{R_m} = 0 $

and substituting for $ R_m $ using $ I = \frac{v_A}{R_m} $

to simplify to $ v_A = 9-I * R_{BATT} $,

indeed the equation of a line.

From the model diagram, we see that a real battery only sources a full 9V when no load is applied. As current increases, supplied voltage decreases linearly, with negative slope equalling internal resistance. Here is just one simple example of how we can learn about a system by perturbing it -- whether theoretically or experimentally. In this case we found the function relating voltage and current by imagining putting a load on the battery. Note that the equation we found is ultimately not dependent on the resistance of this added load $ R_m $.

Real voltage and current measurement devices

Real electronic breadboards

At each tie point on the breadboard the connection between the wire or circuit element lead and the internal conductor of the breadboard is not perfect. The imperfection appears as both a parasitic resistance and a parasitic capacitance in series with the circuit element on the breadboard. The resistance can be on the order of 1 Ω while the capacitance can be on the order of a few pF. Thus if the circuit design incorporates capacitance on this order or if the voltage drop caused by a parasitic 1 Ω resistor is relevant, then either these non-idealities must be taken into account or the electronic breadboard must be abandoned in favor of another approach.

Breadboards are most commonly constructed on an anodized metal backboard. The anodization layer is very thin so if a wire or lead is long enough to contact the backboard then it can penetrate that layer and short to the backboard, which may be at ground or at some unknown floating potential.

On the back of the breadboard there are screws holding the banana terminals in place. On new breadboards these are held away from the work surface by rubber or plastic feet on the backboard. On our breadboards these feet have often long since parted company with the backboard. It is wise to cover the screws with a couple layers of electrical tape.

Real capacitors

Real capacitors include a small but sometimes relevant resistance in parallel with the ideal mode of capacitance. This resistance will be specified on the datasheet for the capacitor.

Electrolytic capacitors have a preferred polarity and cannot support a large current. Thus they are only to be used for DC voltages with small AC fluctuations. If they are installed in reverse polarity, then at best they will function poorly and start to stink as the rubber wadding melts or at worst they will explode and shoot someone's eye out.[1]

Real op-amps

Amplifiers using op-amps unfortunately do not follow the golden rules to the letter. The open-loop gain is not infinite. Therefore the difference between the input voltages is not zero and the current into or out of the inputs is not zero. A realistic model of an op-amp must incorporate a specification for the input offset voltage VOS, an internal voltage that adds to whatever voltage is externally applied to the input terminals V- and V+. The model also incorporates a bias current IB for each input. These are close in real op-amps so the average is specified on the datasheet. However they are not perfectly matched and the difference is specified as the input offset current IOS. All of these non-idealities have the net effect of causing a non-zero voltage, sometimes large, at the output in a negative feedback implementation even when the input is zero. Luckily there are corrective actions available.

Cite error: <ref> tags exist, but no <references/> tag was found