Difference between revisions of "20.109(F09): Mod 3 Day 5 Battery testing"

(→Introduction) |

MAXINE JONAS (Talk | contribs) m (16 revisions: Transfer 20.109(F09) to HostGator) |

||

| (9 intermediate revisions by one user not shown) | |||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

=<center>Battery Testing</center>= | =<center>Battery Testing</center>= | ||

==Introduction== | ==Introduction== | ||

| − | [[Image:Charge-discharge.png|thumb|left|400px]] | + | [[Image:Charge-discharge.png|thumb|left|400px]]Take a look at your cell phone battery. If you have a typical LiCoO2 battery you will notice that it has a '''voltage''' (3.7 V) and a '''capacity''' (e.g. 710mA*h for the Motorola MOTORAZR V3r battery). We know that LiCoO2 has a theoretical capacity of 130 mA*h/g, so it's possible to back calculate the amount of active material as 5.46 g (Try it!). The way Motorola determined the capacity and voltage for their cell phone batteries is by testing them on a Galvanostat. This machine applies either positive or negative current in order to charge or discharge the batteries, identical to the protocol you will be following in lab today. By attaching any battery to a Galvanostat and applying a constant current (1100 mA), the battery will charge in a given time interval. By applying a negative current of 1100 mA it's possible to discharge the battery in that same amount of time. A discharge graph, such as the one shown here, plots voltage vs capacity discharged. The flatter the curve the better, since this means voltage remains constant as the battery is used up. We will be testing every battery through 2 cycles of 10 hours each. |

| − | + | The '''theoretical capacity''' of a battery is the quantity of electricity involved for the electro-chemical reaction within the battery. For our gold nanowire batteries, the theoretical capacity is 510 mA*h/g, a value based on the 15:4 Li:Au ratio and the phase diagram for a lithium-gold alloy. Thus, we can calculate the "'''loading factor'''" for the Galvanostat to be 51 mA/g (theoretical capacity divided by the time to charge/discharge). This tells us how much current to use for a 10 hour discharge. Similarly, it's also possible to calculate the needed current to fully charge or discharge your battery. The mass of every electrode will be a little different, so the charge/discharge rates will be slightly different. But as an example, if one of the batteries has an electrode with precisely 1 mg of active material, then in order to discharge it in ten hours we'd have to apply a negative current of -51 uA. | |

| − | <br><center>1 mg | + | <br><center>1 mg x510 mA*h/g x 1 g/1000 mg x 1/10hr = 51 uA</center><br> |

| − | The electrodes that were prepared during last session were placed in a vacuum oven and dried at 100°C for four hours. They were then moved into a glove box and crimped into a battery. Today instruction will be given on how to | + | |

| + | ==Protocol== | ||

| + | The electrodes that were prepared during last session were placed in a vacuum oven and dried at 100°C for four hours. They were then moved into a glove box and crimped into a battery, with the gold nanowires serving as the batteries cathode. Today instruction will be given on how to measure the charge/discharge on the Galvanostat. | ||

Latest revision as of 19:38, 28 July 2015

Battery Testing

Introduction

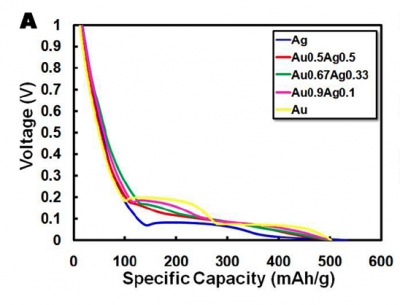

Take a look at your cell phone battery. If you have a typical LiCoO2 battery you will notice that it has a voltage (3.7 V) and a capacity (e.g. 710mA*h for the Motorola MOTORAZR V3r battery). We know that LiCoO2 has a theoretical capacity of 130 mA*h/g, so it's possible to back calculate the amount of active material as 5.46 g (Try it!). The way Motorola determined the capacity and voltage for their cell phone batteries is by testing them on a Galvanostat. This machine applies either positive or negative current in order to charge or discharge the batteries, identical to the protocol you will be following in lab today. By attaching any battery to a Galvanostat and applying a constant current (1100 mA), the battery will charge in a given time interval. By applying a negative current of 1100 mA it's possible to discharge the battery in that same amount of time. A discharge graph, such as the one shown here, plots voltage vs capacity discharged. The flatter the curve the better, since this means voltage remains constant as the battery is used up. We will be testing every battery through 2 cycles of 10 hours each.The theoretical capacity of a battery is the quantity of electricity involved for the electro-chemical reaction within the battery. For our gold nanowire batteries, the theoretical capacity is 510 mA*h/g, a value based on the 15:4 Li:Au ratio and the phase diagram for a lithium-gold alloy. Thus, we can calculate the "loading factor" for the Galvanostat to be 51 mA/g (theoretical capacity divided by the time to charge/discharge). This tells us how much current to use for a 10 hour discharge. Similarly, it's also possible to calculate the needed current to fully charge or discharge your battery. The mass of every electrode will be a little different, so the charge/discharge rates will be slightly different. But as an example, if one of the batteries has an electrode with precisely 1 mg of active material, then in order to discharge it in ten hours we'd have to apply a negative current of -51 uA.