20.109(F07): Transfection

Introduction

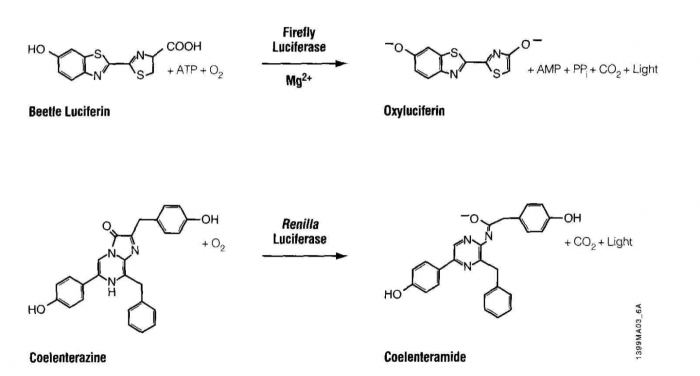

Luciferase is an enzyme that oxidizes its substrate, luciferin. The product, oxyluciferin, emits light in the blue range of the visible spectrum, 440-479 nm. The oxidation reaction is fundamentally different from another light emitting reaction you may be familiar with, fluorescence, as seen with GFP. During fluorescence absorbed light is re-emitted by the excited fluor, often toward the green range of the spectrum, ~505nm. Interestingly our luciferase source, Renilla reformis, has both a luciferase-luciferin pair as well as GFP. Consequently the oxidation reaction can lead to oxyluciferin luminescence and then to fluorescence, through energy transfer to GFP, giving the soft corals a blue-green glow.

Luciferin-luciferase pairs are widely used in nature for courtship, camouflage or baiting. Fireflies (also known as lightning bugs or more technically Photinus pyralis) use an ATP-requiring luciferin-luciferase pair and emit species-specific patterns of light as part of their mating ritual. Bioluminescent bacteria (such as Vibrio harveyi) can be found in symbiotic relationships with marine organisms. The fish give such bacteria a suitable home and in return the bacteria emit light to give the fish “night vision,” or to mask the fish’s shadow, effectively cloaking them from their prey. The usefulness of such luciferin/luciferase pairs was not lost to researchers who began isolating and sequencing luciferase genes from different organisms in order to clone them into useful vectors, such as the one we’ll use today.

Unexpectedly, there is little primary sequence similarity for luciferases from different organisms. This finding will be used to our advantage as we target mRNA from the Renilla luciferase gene for destruction while using the product of the firefly luciferase gene as an unaffected control. On the plasmid we will use, each gene is controlled by a strong constitutive promoter, leading to high expression levels of both luciferases when the plasmid enters a mammalian cell. Other plasmid features that you will be familiar with from experimental module 1 include an antibiotic resistance gene, in this case against the antibiotic ampicillin, that serves as a selectable marker in bacterial cells, a bacterial origin of replication, and multiple restriction sites that can be used for cloning.

In many ways, the assay for luciferase activity is a "standard" assay. The enzyme and substrate must react for a defined time and the amount of product gets recorded. What's a little unusual is that in this case the measured product is light and the light can be quantified using a luminometer. Today’s reactions are slightly more advanced than standard ones in that you’ll perform two sequential measurements. The first reaction is initiated with Beetle luciferin, a substrate for firefly luciferase. The light produced, called a “flash reaction” because it does not persist, will be measured for 10 seconds and then a reagent to stop the reaction will be added. The stop reagent also contains the substrate to initiate the second reaction. Coelenterazine reacts with Renilla luciferase in a “glow reaction” which decays more slowly but you will measure it for precisely 10 seconds so the lumens emitted can be compared to those from the firefly luciferase. There are several attractive aspects to these reactions including the assay’s low cost, high speed, great sensitivity (to attomolar amounts of luciferase, that’s 10-18th!) and wide dynamic range, linear through 7 orders of magnitude. It is also beneficial that there is no endogenous luciferase-luciferin pair in most experimental organisms.

There are two parts to today’s lab. Half the class will begin in the TC facility transfecting MES cells with the luciferase reporter plasmid and siRNAs. The other half of the class will begin by testing some control extracts from transfected cells to become familiar with the luciferase assay and analysis of the data that is generated. Midway through the lab period, the groups will switch places so everyone will have an opportunity to perform both protocols.

Protocols

Part 1: Transfection

DNA can be put into mammalian cells in a process called transfection. Mammalian cells can be transiently or stably transfected. For transient transfection, DNA is put into a cell and the transgene is expressed, but eventually the DNA is degraded and transgene expression is lost ("transgene" is used to describe any gene that is introduced into a cell). For stable transfection, the DNA is introduced in such a way that it is maintained indefinitely. Today you will be transiently transfecting your cultures of mouse embryonic stem cells.

There are several approaches that researchers have used to introduce DNA into a cell's nucleus. At one extreme there is ballistics. In essence, a small gun is used to shoot the DNA into the cell. This is both technically difficult and inefficient, and so we won't be using this approach! More common approaches are electroporation and lipofection. During electroporation, mammalian cells are mixed with DNA and subjected to a brief pulse of electrical current within a capacitor. The current causes the membranes (which are charged in a polar fashion) to momentarily flip around, making small holes in the cell membrane that the DNA can pass through.

The most popular chemical approach for getting DNA into cells is "lipofection." With this technique, a DNA sample is coated with a special kind of lipid that is able to fuse with mammalian cell membranes. When the coated DNA is mixed with the cells, they engulf it through endocytosis. The DNA stays in the cytoplasm of the cell until the next cell division at which time the cell’s nuclear membrane dissolves and the DNA has a chance to enter the nucleus.

Two days ago, cells were prepared for you at a density of 1 X 10^5 cells/well in all six wells of two six-well plates.

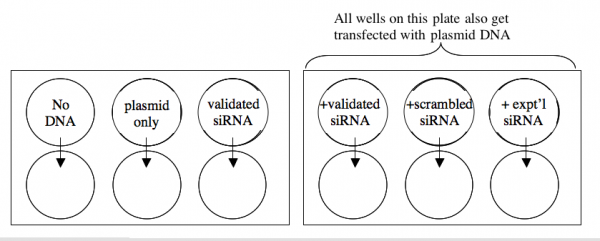

A schematic of your experiment is shown below.

All manipulations are to be done with sterile technique in the TC facility. In addition, since you will be working with RNA, it is important to wear gloves whenever you are handling the transfection reagents. This will protect them from degradative enzymes on your fingers.

Timing is important for this experiment, so calculate all dilutions and be sure of all manipulations before you begin.

For each lipofection you will need

- Carrier: 3 ul Lipofectamine 2000 in 50ul OptiMEM

- DNA: 20 ng of psiCHECK2 in 50 ul OptiMEM and/or

- siRNA: 10 pmoles in 50 ul OptiMEM (final tx’n concentration of 10 nM)

1. Dilute enough carrier for 12.5 lipofections. Let the dilution sit in the hood undisturbed for at least 5 minutes but not more than 30.

2. All the lipofections will be done in duplicate with 20 ng of DNA/well and/or 10 pmoles of siRNA/well. Prepare a cocktail with enough material to perform both replicates. The following table may be helpful for your calculations.

| Tube | [DNA] stock | Volume DNA needed | [siRNA] stock | volume siRNA needed | OptiMEM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No DNA | --- | --- | --- | --- | 100 ul |

| plasmid only | 20 ng/ul | --- | --- | ||

| siRNA only | --- | --- | 10 pmol/ul | ||

| plasmid+siRNA (validated) | 20 ng/ul | 10 pmol/ul | |||

| plasmid+siRNA (scrambled) | 20 ng/ul | 10 pmol/ul | |||

| plasmid+siRNA (experimental) | 20 ng/ul | 10 pmol/ul |